Last night, I placed my first real trade on a prediction market.

Not the flashy kind. Not the “all-in” kind. Not the kind you see people brag about online. I wasn’t chasing a miracle payout or trying to beat the world in one move. I wasn’t reckless, and I wasn’t emotional. At least, that’s what I thought.

I did something much more ordinary, something most beginners do on their first day.

I bought what looked like a safe outcome and that’s the part nobody warns you about: the “safe” trades are often the ones that teach the hardest lesson. They don’t look like gambling, so you don’t treat them like a risk. They feel like common sense, so you assume they can’t hurt you. But in a prediction market, “safe” usually means expensive and expensive means there’s very little room for error.

That’s why this story matters. This article is a clean, step-by-step record of what happened, what I felt in real time, and what the trade revealed about probability, pricing, and the danger of confusing “likely” with “low risk.”

The Setup: A Trade That Looked Obvious

I was trading on Kalshi, a platform where users trade YES/NO contracts on real-world events.

The market:

Baltimore Ravens vs Pittsburgh Steelers — Will Baltimore win?

First: what “82%” really meant

When I saw that the market priced Baltimore at 82%, it didn’t mean Baltimore was guaranteed to win. It didn’t mean the game was basically over. And it didn’t mean I had discovered some smart edge.

It meant one thing—and only one thing.

If 100 informed people were forced to put real money down, the average belief was that Baltimore would win about 82 times and lose about 18 times. Nothing more, nothing less.

In other words, the market was saying, “Baltimore is very likely—but not certain.”

That distinction matters far more than it sounds.

Why the trade felt safe

As a human, I don’t experience probabilities as numbers—I experience them as feelings.

Fifty percent feels like a coin flip. Sixty percent still feels uncertain. Seventy percent feels likely. And eighty percent feels safe.

So when I saw 82%, my brain didn’t register it as a probability. It translated it emotionally. What I heard wasn’t “82%.” What I heard was, “This almost can’t fail.”

That emotional translation was the moment the risk entered the trade.

What clicking YES · Baltimore actually did

When I clicked YES, I wasn’t saying, “I think Baltimore is good.”

What I was really saying was, “I am willing to pay a high price because I believe Baltimore will win.”

At 82%, the market price reflected that belief. Each contract cost about $0.83, meaning I was paying almost the full dollar upfront for that confidence.

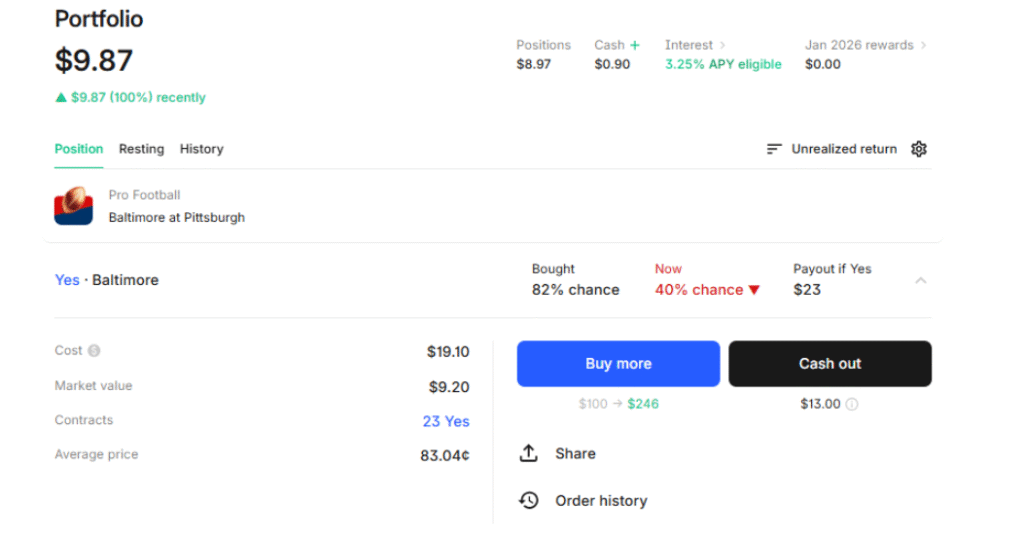

Why I paid $19.10

I paid $19.10 because I bought 23 YES contracts.

Buying 23 YES contracts meant I was purchasing 23 separate $1 payouts—each one would pay only if the event happened. There was no multiplier and no bonus. Just $1 per contract if Baltimore won.

At the time, each contract cost about $0.83 on average. So the math was simple:

23 × $0.83 ≈ $19.10

That $19.10 was fully at risk. It was locked in the moment I clicked buy. If Baltimore lost, it was gone—no partial refund, no “almost,” no consolation prize.

Each contract represented a very simple promise:

If Baltimore won, I would receive $1.

If Baltimore lost, I would receive $0.

Why my best-case outcome was only $23

What I bought were 23 separate YES contracts. Each one was a simple promise: if Baltimore won, that contract would pay me $1. No bonuses, no multipliers, no extra upside. Just $1.

So even if everything went perfectly if Baltimore played well, held the lead, and won the game—the most I could ever receive was $23. That was the ceiling. There was no scenario where those contracts could pay more than that.

But I didn’t get those contracts for free. I paid $19.10 to buy them.

So in the best possible outcome, I would receive $23 back, which means my actual profit would be $3.90. That was the full reward for being right.

Looking at it plainly, I was risking $19.10 to make $3.90.

That imbalance is what made the trade dangerous. Not the game itself, not the team, and not the outcome—but the fact that I had put a large amount of money at risk for a very small return.

Why that trade-off is dangerous (this is the key)

At first glance, the trade looked reasonable. The odds were high, the potential gain was small, and everything felt controlled. It didn’t look reckless. It didn’t feel like gambling. It felt sensible.

But hidden inside that comfort was a reality I didn’t fully appreciate at the time: I was risking about five times more than I could ever make.

That imbalance changes everything. When the downside is much larger than the upside, a single loss can erase multiple small wins. One bad outcome doesn’t just sting—it overwhelms all the progress that came before it.

The margin for error in that kind of trade is tiny. There’s almost no room to be wrong, no room for bad luck, and no buffer for unexpected changes. What felt “safe” on the surface was actually fragile underneath.

Why confidence became the risk

My confidence didn’t come from better information. It didn’t come from an edge the market had missed or from any superior analysis on my part. I wasn’t seeing something others couldn’t see.

My confidence came from a number—82%. And from the feeling of safety that number created.

That was the trap.

The market had already priced that confidence in. By the time I clicked BUY, the comfort I felt had already been paid for. The safety was gone.

All that remained was the risk.

The Hidden Assumption I Didn’t Question

Like most beginners, I was carrying an assumption I didn’t even realize I had: if something is very likely, it must be safe.

But on prediction markets, likelihood is already baked into the price.

An 82% chance doesn’t mean “almost guaranteed.” It doesn’t mean “low risk.” And it definitely doesn’t mean “smart trade.”

What it really means is this: I was paying almost the full reward upfront.

At 82%, I was risking about $0.82 to win $0.18 on each contract. I was putting up most of the money while leaving myself very little upside in return. That imbalance wasn’t obvious to me at the time.

I didn’t fully appreciate that trade-off until the market moved—and by then, the lesson was already in motion.

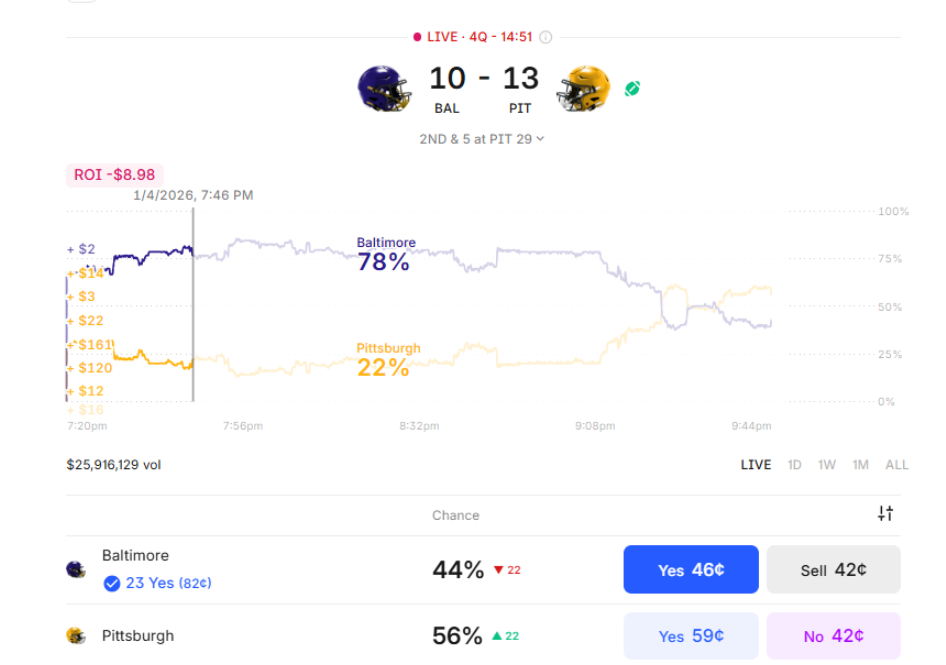

When the Game Changed, the Price Changed Faster

As the game progressed, things started to change. Pittsburgh began playing better. Baltimore struggled. The momentum slowly shifted.

Kalshi’s prices adjusted in real time. Baltimore’s odds didn’t drift—they collapsed, falling from 82% to around 40%.

The game wasn’t over. No final whistle had blown. Nothing had been decided yet. But the market’s belief had changed.

That was the moment the lesson hit me: on prediction markets, you can lose money before the event is over.

The reason is simple but unintuitive—prices don’t track final truth. They track belief. And belief can change long before reality is settled.

The Emotional Moment: Hold or Cash Out

At that point, the value of my position had dropped sharply. I could cash out for less than I had put in, or I could hold and hope Baltimore recovered.

That was the hardest moment—not because of the money, but because of sunk-cost thinking. I felt the pull of a familiar thought: I already put in $19.10. I can’t walk away now.

But that wasn’t the right question.

The correct question was simpler and far more revealing: If I had this remaining money as cash right now, would I place this bet again at these odds?

That question cuts through emotion and exposes reality.

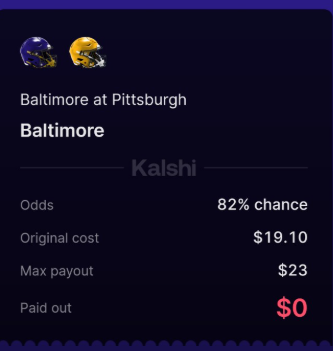

The Resolution: Probability Is Not a Promise

The game ended. Baltimore lost.

With that, the outcome was final. My YES contracts paid $0. The trade was settled. The money was gone.

Nothing glitched. Nothing was rigged. Nothing was unfair.

This was simply one of the 18 losses out of 100 that an 82% probability always allows for. The outcome had always been possible, even if it didn’t feel that way at the start.

I didn’t lose because I was reckless. I lost because I misunderstood the difference between price and probability.

The Core Lesson: Why “Safe” Trades Are Dangerous

Here is the lesson that matters most to me: high-probability outcomes are expensive, and expensive outcomes leave almost no margin for error.

When I buy a favorite, I’m risking a lot for very little in return. The upside is small, but the downside is large. One loss can wipe out several small wins, even if I’m right most of the time.

And that’s the part that’s easy to miss. Being right often isn’t enough. To make money, I have to be right more often than the price already assumes.

That’s an extremely difficult standard to meet, especially for a beginner.

Why This Happened on My First Trade (and Why That’s Normal)

This experience wasn’t unique. In many ways, it’s almost a rite of passage.

As a beginner, I was naturally drawn to favorites, to high probabilities and outcomes that felt obvious. Those trades look sensible. They feel safe. They give the illusion of control.

Markets understand this psychology. That’s why favorites are often slightly overpriced. They’re emotionally attractive, easy to justify, and, for learning purposes, surprisingly poor environments.

Live sports amplify all of this. Prices move violently, emotions spike, and a single play can flip probabilities in seconds. What looks stable one moment can unravel the next, leaving very little time to think clearly.

That combination, favorites and live action is exactly where beginners learn the hardest lessons the fastest.

What I’d Do Differently Next Time

From this single trade, a few clear rules emerged for me.

First, I need to avoid favorites above 75%. They feel safe on the surface, but the risk–reward trade-off is terrible. I’m risking too much for too little, with almost no room for error.

Second, I need to avoid live sports while I’m still learning. They move too fast, emotions run too high, and the price swings are unforgiving. It’s the hardest environment to think clearly.

Third, I have to decide my exit rules before I enter a trade. If I wait to figure it out under pressure, I’m no longer making decisions—I’m reacting.

Fourth, I need to trade small until the mechanics are second nature. Early trades aren’t about making money; they’re tuition for understanding how pricing, movement, and psychology really work.

Finally, I have to ask the right question. Not “Will this happen?” but “Is the market’s price wrong?” That shift in thinking changes everything.

Why I need to avoid favorites above 75%

I need to avoid favorites above 75% because, by the time something looks that likely, I’m already paying almost the full reward upfront.

When I buy a trade at 75% or higher, I’m not paying for upside—I’m paying for comfort. I’m putting most of the money on the table just to win a very small amount back. That means I’m risking a lot of money for a very small gain.

The problem with that setup is simple: there’s almost no room for error.

If everything goes right, I win a little.

If anything goes wrong, even once, I lose a lot.

So one bad outcome can wipe out many small wins. Even if I’m right most of the time, I can still end up losing money because the price already assumes I’ll be right that often. I’m not being rewarded for being correct, I’m being punished for being even slightly wrong.

What makes this especially dangerous is how it feels. High-probability trades feel safe. They feel reasonable. They feel controlled. But that feeling is misleading. The safety I feel is something I’ve already paid for in the price. By the time I click buy, the protection is gone.

All that’s left is exposure.

That’s why favorites above 75% are dangerous for me, not because they don’t win, but because when they lose, they hurt far more than they ever help.

How I end up paying almost the full reward upfront

On a prediction market, the percentage I see is not just information — it is the price.

So when I see something priced at 75%, 80%, or 82%, what that really means is this:

To win $1, I have to pay about $0.75, $0.80, or $0.82 right now.

Nothing is hidden. Nothing comes later. The market is charging me upfront for how likely the outcome is.

So when I buy an 82% favorite, I’m not paying $0.10 or $0.20 to win $1. I’m paying $0.82 to win $1.

That’s how the reward gets used up before the trade even starts.

The simplest and most precise way to think about it is this:

- $1 means certainty — “This definitely happened.”

- $0 means impossibility — “This definitely didn’t happen.”

- $0.82 means belief — “We think this will happen about 82% of the time.”

So yes, the price is simply the market’s confidence, expressed in dollars instead of percentages.

Why the price works this way

Each contract has only two possible endings. It will eventually become either $1 or $0.

- If the event happens, the contract becomes $1.

- If it doesn’t, the contract becomes $0.

Before the event is over, the market is constantly asking one question: What do we think this will turn into?

At 82%, the crowd is effectively saying, “Most likely this ends up as $1—but not always.”

So the market settles on $0.82.

Why this explains why I was gaining so little

When I bought at $0.82, the most that contract could ever grow was:

$1 − $0.82 = $0.18

That $0.18 represented the remaining uncertainty.

It was the only profit left in the trade.

Everything else—the confidence, the likelihood, the feeling of safety—had already been paid for upfront.

The clean mental model that made it click

Price = confidence converted into dollars.

Profit = whatever uncertainty is left.

So:

- High confidence → high price → small profit

- Low confidence → low price → large profit

The sentence that finally locked it in for me

I wasn’t buying a chance to win big — I was buying a nearly finished outcome, and there wasn’t much room left for it to move.

How this quietly shifts all the risk onto me

Here’s where it becomes dangerous.

If I’m right:

- I make a small amount (that $0.18)

If I’m wrong:

- I lose almost everything I put in (the $0.82)

So the trade becomes unbalanced:

- Small reward when I’m right

- Big penalty when I’m wrong

That imbalance exists because the price was high, not because the outcome was bad.

Final Reflection

Last night’s trade didn’t teach me how to predict football games.

It taught me something far more important.

Markets don’t reward confidence, they reward correct pricing.

Probability is not safety.

Likely does not mean cheap.

And being right means nothing if you paid too much to be right.

That lesson cost me money.

But it may have saved me far more.

Leave a Reply